Ana's Knitting

A well-stocked pantry in Cristalândia holds jars of sweets made from fig, rice, squash, papaya, peanut and corn. On the kitchen table, a hand-embroidered linen protects the cornmeal cake from flies while it cools. And as the embers glow in the wood-burning stove, the fresh-drawn milk skims over with a yellow layer of fat. Most people are only one generation away from the farm, so all this work of transforming nature is not an inconvenient burden but a way to still participate in the cycle of life. For the pequi fruit rots in the road, and the lemongrass wilts in the sun. Better to bake these things into cake, stew them into candy, boil them into soap or knit them into clothes before their gifts return to the earth.

Sostenes

I first photographed Sostenes as a boy, so it was no surprise that I didn’t recognize him as a man, obscured by the grate in the window at his grandmother’s house. He called my name anyway and came out to assure me it was him. Crime is hard to see in Cristalândia. But one by one, the grates and gates emerge, as walls rise higher, sprout razor wire and hoist video cameras that peer into the street. No one saw anything, he said, so they probably came over the back wall. Could’ve been the guys at the truck stop, passing through town… boys, really, still figuring out what it means to be a man.

Candle for Dona Araújo

Beth would go every Sunday morning, and I usually went with her. I’d lived with other families who went to mass every Sunday, but this ritual seemed more direct. After all, she was the one who’d lived with her mother at the end. "Throwing water" is how people wash the tiled floors in their homes, so the method for this tile is the same, and spigots are scattered throughout the graves to make the job easier. The sloshing water both softens the dirt and pushes the soap into every corner. Gravity then pulls the suds to the edge where they drip into pools on the ground. Kneeling, Beth wipes the water away in slow circles, massaging the hard surface and coaxing a gentle shine out of her mother's faded photograph, sealed behind plexiglass on the grave. She sprinkles flowers at the end, because they glow in the Sunday morning light radiating off the clean tile. Others prefer candles.

Girl in the Afternoon

She always drew figures on the houses she rented, but no one remembers her name. She may have been the one to peel the circular campaign sticker off the wall, or maybe it was already gone when she started. So it's hard to say whether the politician's face was simply an intrusion on prime drawing space or whether she anticipated how the radial strips of old glue would play into her creation.

Martinha Feeds the Birds

Over 4,000 species of fruit trees grow in the Brazilian savannah, a generous buffet for the over 400 species of birds who feed on them. The birds could portion out the trees evenly, and each bird species would still get ten different fruits all to themselves. But diplomacy would take time away from eating. In Martinha's garden, precision is limited to the pressure of the knife along the flesh of the papaya and the alignment of the peels on the ground. The rest is up to the birds. She gardens in order to feel the life that courses through nature, not to control its wildness.

Water Tower at the Community Center

When I wanted to swim laps, Maria do Carmo would take me to the private club where a high, transparent wall enclosed the property, more a reminder of privacy than a deterrent against crime. But the old community center serviced the whole town. Its doors were rarely locked, so you could wander inside and soak in the expanse – a large stage, two bathrooms, a concession stand and lots of space. The simple architecture flexed to support the needs of everyone, making large parties feel intimate and small parties feel ample. Good architecture adjusts to the needs of a new tenant, performing an effortless illusion of physics and space.

Maria Cecília

Maria Cecília wasn’t even a consideration when I first met her mom, although I’m sure Meire had always wanted kids. She herself had seven siblings, and the living ones always gathered at her parents’ house, even her oldest brother who lived fifteen hours away. Sometimes, Meire’s aunt would walk across the street to join, too, trailing her own crew of five. The family tree stretched into every neighborhood and grew in every direction, spilling into the surrounding states. Initially, people loaded their kids up in the car, but eventually the kids drove themselves. By the time Maria Cecília was born, Meire already had three grand nephews, so her daughter has grown up playing with second cousins, first cousins and half-cousins – hide-and-seek, telephone, dress-up and other games that rearrange the generations.

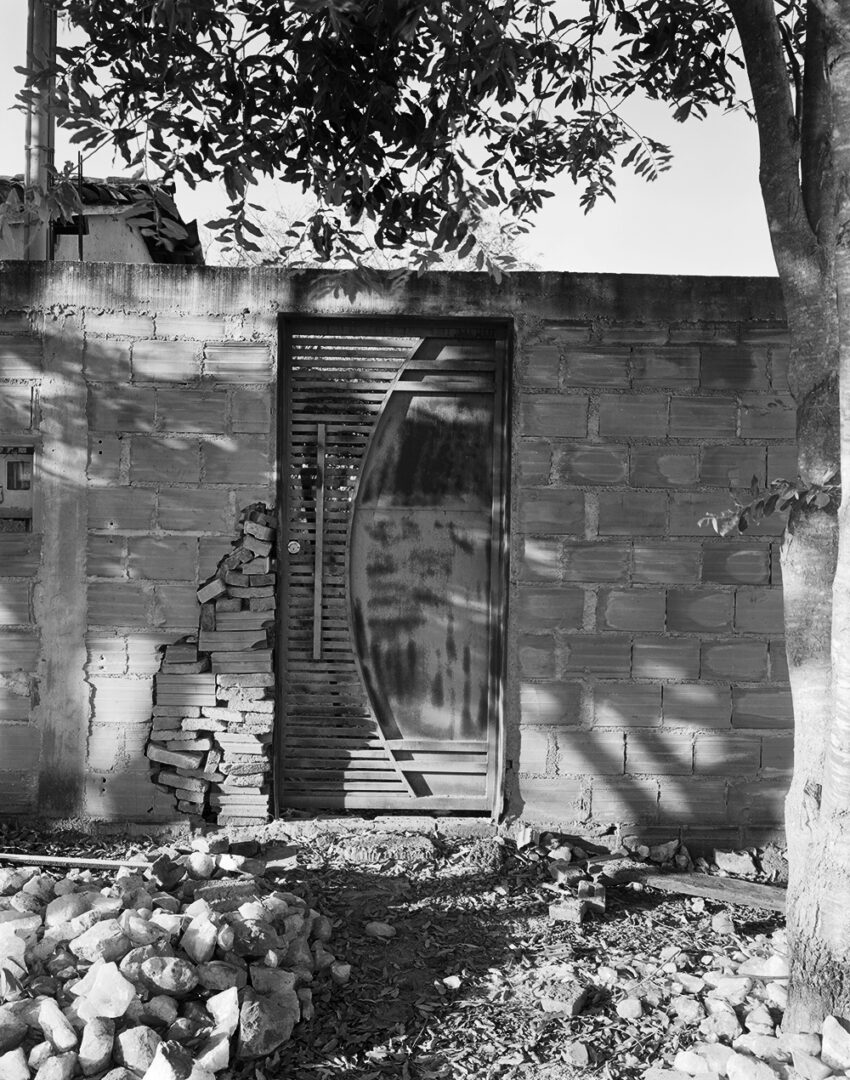

Raimundo's Front Gate

People can choose between two ceramic factories in town. One makes roof tiles, the other bricks. It’s a steady job for those who prefer to stay in town. In turn, the bricklayers, roofers, mudders, electricians, painters and plumbers also join the enterprise. Piles of material fill people’s yards, patiently awaiting their turn in the assembly line. Work structures your day and builds purpose into your energy. It secures you in place and confirms you belong.

Ceiça and Daví

The priests in Cristalândia use the same seven books as all Roman Catholic churches to guide them through the various services. These books take vast questions of spirituality and condense them into objects that are relatable and handheld, manuals for moving through the cycles of life. The other definition of “manual” comes from the same Latin word for “hand”, but the Oxford dictionary clarifies that “handheld” manual evolved separately from “by hand” manual, because they describe two separate uses of the hand. One references size; one references labor. Yet both versions of “manual” describe our relationship with the world through the intimacy of touch. Touch is physical and confirms the concrete, reassuring us that the miracle of life is real.

Ataís and Thadilla

The schools in Cristalândia have always been good. Ataís moved her family to town because of them, and Thadilla has thrived there. Cristalândia is the seat of its Catholic diocese, so establishing a school was a priority from the beginning, run by the nuns and nurtured daily by the bishop. The school, the nunnery, the cathedral and the bishop's house are all lined with crystal – rough ones, straight from the mine. It's a common building material in town, but in this family of buildings the crystals remind people where wealth originated and how it's applied. The church recently sold the school, but its crystals still radiate.

Fencepost at João's House

The old houses never have insulation. The heat would crush you if they did. The ceilings were designed to be open so that the hot air rises up and away from the living space below. You can see straight into the rafters – rough beams, cut on-site and thick enough to hold the rows of heavy ceramic tile. Planing down to true-square wastes good wood and precious time, so these beams curve and arc as they lift, soaking up as much heat as possible. Because even a slow, creeping breeze is enough to coax the suffocating heat off your skin and into the beams above, swaying the wisps of your hair with waves of cool.

Waiting for Soccer Practice

By the time crystal extraction reached peak volume, they had already built an airport to haul the stones away, the first leg in a journey all around the world. No structure was built. The pilots simply followed the marks on the ground to know where to land. Plane tires, truck tires and bike tires; feet, hooves and paws; lines, circles, streaks and figure-eights; cracks, ruts and stains. The soccer arena is much easier to find, but the boys mark its walls, too, just in case.

The Hole at Sunset

The big machines only come when there's money to rent them. Hoses snake up and down the dirt slopes in anticipation of their arrival, consolidating rain water into lakes so that the active holes are dry and always ready to resume digging. Lushness is promising in the heat of the arid savannah.

Edvaldo's House

It took a few years for production to justify building a town. But eventually, the single homes began multiplying, until clusters of new construction packed the narrow streets. Back then, bricks were solid, not hollow, and you stacked them two rows deep to form thick walls that held the coolness in. If the budget allowed, you’d skim cement over the entire surface to seal the bricks and facilitate painting. But the outside remained bare, because your neighbor would soon add their wall right up against yours. In a town, walls are shared. Their house supports yours, helps mend your cracks, celebrates your growth and holds your warmth in.

Shameless Mary in the Sidewalk

If you were to call “Mary!” into a crowd of Brazilian women, the majority would turn their heads. Cristalândia is no different. Using their full names narrows the possibilities – “Mary of the Ascension” or “Mary of Perpetual Help” or “Mary of the Apparition”. But it’s practical names like “Mary of the House on the Corner” or “Mary of the Fancy Car” or “Mary of the Three-Legged Dog” that actually pinpoints the individual. This plant, though, doesn’t need clarification, so it’s just called “Shameless Mary”. It grows everywhere, shamelessly. Even if you prefer the English version, “Impatiens”, the name highlights the grace and whimsy necessary to thrive in the pressures of the tropical sun, which could be why so many parents choose Mary, hoping their daughter will live up to the challenge. Surely the mother of Jesus would feel honored as she laughed.

Under the Mango Tree

You hear the macaws more often than you used to. Their squawk pierces the air and surrounds you in disorienting alarm. The savannah has a wealth of fruit trees, but it's the mangos that the macaws are after. Their beaks can break your finger and easily rip the tender, stringy flesh away from the pit, clutched in the two pairs of toes on each foot. As agribusiness inches closer to Cristalândia, the mango trees have come down to make way for crops that are flat and easily harvested by machines that can't be bothered to steer around shady trunks. The macaws come to feast on the mangos that are still plentiful in small groves scattered around town. They arrive in pairs – mates for life – an echo of both form and sound, seeking shelter in each other more than the trees.

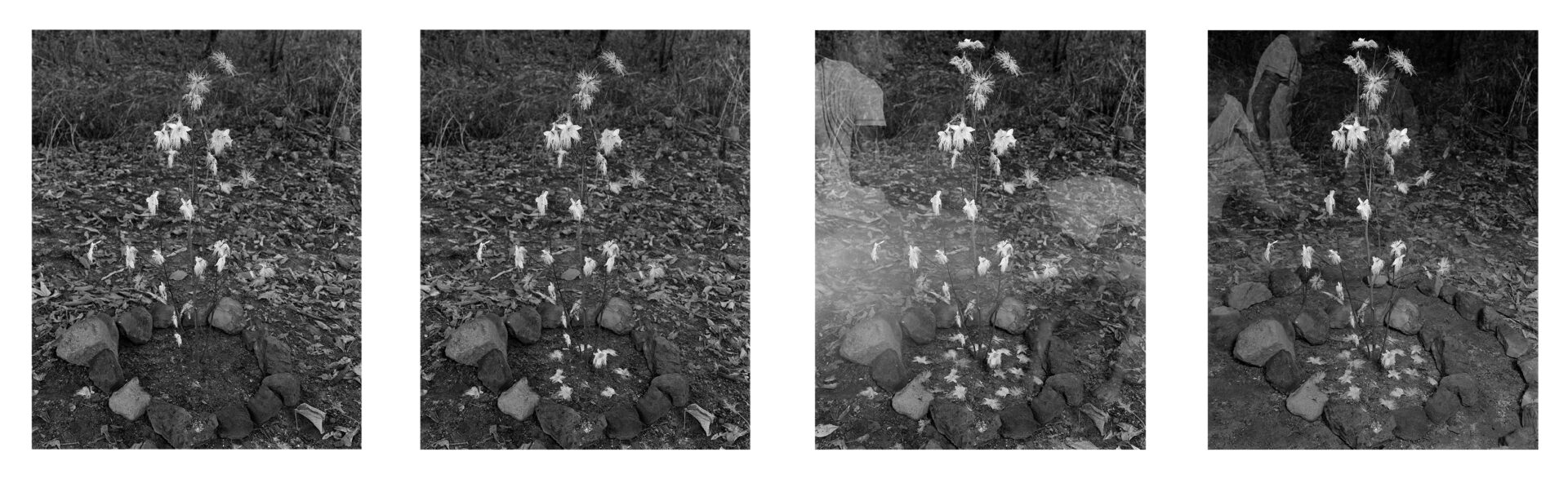

Heitor, Gabriel & Eduardo Rebuild the Pequi Tree After the Fire

Cristalândia has only two seasons: the rainy season and the ashy season. Most people smell the smoke, but few know who sets the fires. And everyone sweeps the ash out from their houses afterwards. However, the pequi flowers hang high above the flames, so that only a few wither from the heat. The rest drift down to the ground, tired but whole. The boys work with finesse, though, and easily skewer both kinds onto their new home.

The 8x10 view camera takes time to reposition, so it's much better to keep the camera in one spot and let the world evolve in front of it. It's impossible for me to know exactly where the boys' figures will appear in the frame each time I pop the flash during the one-minute exposure. But the boys don't really know what they're building either. We both work from instinct.

As the sun sets, the exposure gets longer, and each pop of the flash serves to intensify the glow of the flowers against the fading light of the background. The lengthy, mechanical process of operating a view camera has always required the photographer to collaborate with the subject. Even the wispy grass participates in the exposure as it sways in the wind. But the boys have evolved beyond participants and into co-directors, as we confer with each other the right moment to start, stop and start again.

Maps say Brazil – Tocantins, perhaps.

But that's not how you'll find it.

You'll recognize Cristalândia by your experiences there – by the marks you left behind. Walk slowly, though, because marks are small and illusive.

The marks we leave are often only as permanent as an elongated shadow and as private as the discoveries made in this mutated form.

Marks soon fall to the ground. They accumulate under your feet and are pressed into the history of the earth, so that when the rainwaters rise, your toes can sink down into the mud and rearrange the generations.

When the big machines come, the miners wrestle marks back to the surface. The mechanized shovels exhume ancient mountains, sift through their secrets and scatter them on the hillside to dry. It's a good business, when business is good... when the big machines come.

For now, the grasses grow, and the grasses burn, wrapping the marks in green and guarding them with sheets of fire and fresh ash.

The grasses guard your marks, too.

And they'll find them, when the big machines come.